If you could be any cartoon or comic book character, who would you be? And who would your girlfriend/boyfriend be…

Astro boy! Tetsuuan Atomu: I am a robot and proud... I could fly anywhere. My boy/girl friend would be Kerokerokeroppi. — Craig Flanagin, God is My Co-Pilot (1996)

(▰˘◡˘▰)

One of the great pleasures of web browsing is unearthing a late-90s fansite still intact: colorful, cutesy, and colloquial. Allan Hise’s online guide to the now-defunct NYC punk outfit God Is My Co-Pilot checks all three of these boxes, offering a much-needed resource for those wanting to learn just about anything about the band. Though their prolific discography spanned 30-odd discs and hundreds of short songs from ‘91 to ‘98, you won’t find much more than their best-of collection available on Spotify. Five minutes of an unidentified gig exist on YouTube, but that’s all the footage of them you’re likely to ever find.

Becoming a God Is My Co-Pilot fan in 2021 takes a scholarly dedication to sub-culture, wading from the shallow, streamlined waters of the corporate internet and into the backwater world of file-sharing and .html-coded ephemera. That dearth of easily-accessible information all but ensures their obscurity outside of free-improv obsessives and punk historians, but I think they’d prefer it that way. Through my exploration of the GodCo discography in recent weeks, I’ve learned not just how ahead of the time their ethos and aesthetic were, but also how similar countercultures from different eras turn out to be once you dig into the primary source material.

(▰˘◡˘▰)

Bump a few GodCo records back to back. Scour the liner notes and sleeve art if you’ve got ‘em. Let the cacophony and beat poetry do their thing — don’t overthink it. Chances are you may only remember two or three of the songs. The majority of them clock in at around a minute, comprised of enough off-kilter percussion and atonal guitar skronk to let vocalist Sharon Topper rattle off some stanzas of free verse; sometimes spoken, sometimes sung in the sing-song register your inner monologue uses to help recall trig formulas or items on a grocery list.

While the tracks themselves come and go like daydreams, you will walk away from each record with an intimate understanding of just what made its ever-changing roster of members — especially husband/wife duo Craig Flanagin and the aforementioned Sharon Topper — tick. Here’s an extremely abridged list of just some of the things they dig, based on their music:

||| Boys, girls, cats, Ghibli flicks, Ornette Coleman, The Minutemen, Little Women, Hello Kitty, learning languages, folk songs, childhood, dreams, sex, drugs, violence, Moomin, and Björk. Did I mention cats? |||

While there are some more concrete or pointedly political songs in the GodCo, especially on 1993’s Straight Not, which meditates on bisexuality and gender identity, most of their albums function as multimedia diaries: spiritual precursors to shitposting accounts/blogs/finstas, et al. The process of recording — sloppily mashing out hardcore punk songs or composing eerie sound collages or staging improv comedy sketches — is the art itself. Rockists search for meaning (explicit or implicit) conveyed through performance, but interviews with Topper and Flanagin reveal vehemently anti-rock, pro-jazz sentiment. Their performance is the meaning. Assembling a circle of collaborators and curating an aesthetic is an art in itself. GodCo make you feel like a part of it.

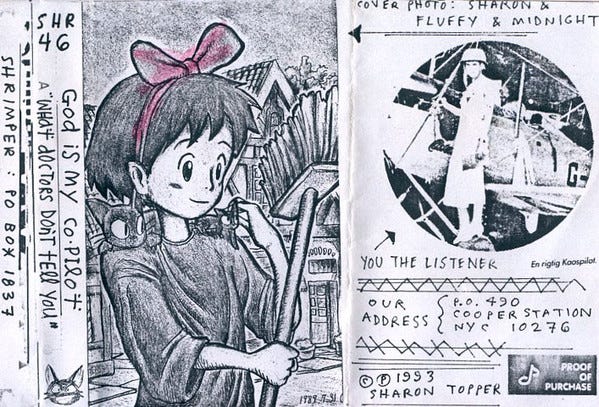

It helps that they’d fit right in to the current alt social media zeitgeist, juxtaposing appropriated pics of anime characters or cute Sanrio mascots with GodCo’s own shocking text for comedic/surrealist effect. Peep the pen-scrawled notes on the cover art below: an early iteration of a “me irl” post.

Even more prescient is the band’s side project: a self-proclaimed “Moomincore” trio named for the silent, nomadic species dreamed up by Moomin cartoonist Tove Jansson. While Flanagin and Topper’s interpretation of the Moomincore aesthetic is primitive, vaguely spooky punk, the term has still been used in recent years to describe the cozy, whimsical mythos of Jansson’s art (and proves that arbitrarily slapping the “-core” or “-punk” on a word to create a new art movement was a practice long before social media was a thing). You’ve got to wonder how GodCo would’ve fared in today’s landscape of curated Instagram pages and ultra-specific architectural movements in Animal Crossing.

(▰˘◡˘▰)

There are a handful of God Is My Co-Pilot compilations out there, including the aforementioned best-of collection that’s on Spotify. None of them, however, makes as good of an introduction to the band as choosing a release at random and diving in. It’s like bumping a best of Ornette Coleman collection: serviceable in that they contain a bunch of cool jams by talented musicians, but disappointing in that you’re likely more interested in the gestalt of a recording session than any particular song.

Instead, I’ll provide what I believe are some good entry points into the GodCo universe based on your taste. Or you could just pick the ones with the coolest cover art. That’s what I’d probably do.

What Doctors Don’t Tell You (Shrimper, 1993)

You can probably guess why this was the first GodCo record I listened to. That traced Kiki’s Delivery Service is everything I’ve ever wanted in cover art. That’s not the only reason, though. Notably, What Doctors Don’t Tell You is their sole entry in the Shrimper Records catalog, so I always noticed it while poking around on Discogs looking at old Mountain Goats tapes. John Zorn plays saxophone on many of the songs, which is also a pretty big draw.

As it’s the only GodCo record released exclusively on cassette, What Doctors… features some of the band’s more straightforward and digestible work. Especially on side B, the playing will sound somewhat familiar to those who dig early stuff by Sonic Youth or Minutemen. Those enlisted to handle the rhythm section (which could be any combination of the 7 people credited on drums and/or bass) stick to funk adjacent grooves while guitar and sax splatter the remaining canvas space with sound. Melody takes a backseat to texture: twangy and serrated, half-improvised but clearly orchestrated to a certain degree.

The band performs with all the confidence and reckless abandon of delinquents who’ve signed up for the middle school talent show with intent to shock. And Toppers’s puerile vocals are undeniably charming, even (or especially) when they’re ordering you to “suck, suck, suck my dick.” I can’t help but imagine a vice principal turning beet-red offstage. And true to the record’s quasi-live production, GodCo punctuate their songs with other artists’ stage banter, including a sample of Charles Mingus demanding silence from his audience (which was, interestingly enough, recorded in-studio for a fake live album). Ever the meta-textual pranksters, these guys.

Getting out of Boring Time, Biting into Boring Pie (Quinnah, 1993)

Maybe you’re in the mood for something weirder. Boring Time, released the same year as What Doctors Don’t Tell You, offers a glimpse of GodCo at their most inscrutable. 7 members make up the band this time around, though you’d be pressed to pick out any one individual’s contributions from the record’s collage-like arrangements. There’s as much didgeridoo as there is guitar here, though most of what you’ll hear on Boring Time can be filed under “objects” and “machines” on the credits sheet.

“Well You Needn’t" is largely dissonant interpretation of the titular Thelonious Monk composition, featuring poetry about plaid skirts, an apocalyptic whirring, and the sound of something being ripped apart. “Ant Circus” eschews anything resembling tonality, building a soundscape around percussion. It sounds like a drum kit being dropped down a flight of stairs or an entire library of Looney Tunes sound effects playing at once. Closer “Furbearing (Mammal Mambo)” corrals the cacophony into a hip-shaking groove and a (relatively) anthemic chorus.

“you're a mammal I'd like to hold / warm blooded mammal / snuggly & furred”

To offset the more experimental instrumentation, Topper and Flanagin keep things simple on the lyrical front, making use of anaphora and easily-shouted phrasing. “Stop” is a polemic against self-doubt, “Look In…” challenges listeners to consider the societal factors that cause women to stay in toxic relationships, and “Looks Like It Feels” waxes philosophical about butts. Overcome the initial shock of the didgeridoo on this record and you’ll find it’s a rewarding listen — even catchy, on occasion.

An Appeal to Reason (Runt, 1997)

I bought this lil 7” single sometime in high school, but I don’t think I knew much about it at the time. If my memory’s correct, I found An Appeal to Reason at a Half-Price Books and thought the art looked cool. Just a hair over 5 minutes long, the EP opens with the poppiest track in the band’s catalog: “Steal Yr Girlfriend”. It’s a chaotic evil anthem that taps into the era’s grunge ethos without sacrificing GodCo’s identity. If I were sequencing a best-of catalog, I’d put it right at the top. They don’t let off the gas for the remainder of the record, chord-mashing like a grindcore outfit. Need a quick fix? You’ve got it.

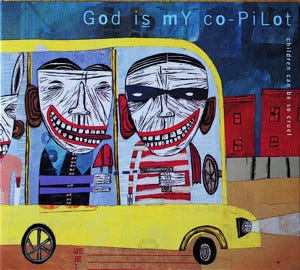

Children Can Be So Cruel (Miguel, 1998)

Sure, it’s a collection of tracks from the cutting room floor, but it’s short enough to bump on the way to work while diverse enough to represent most of GodCo’s musical inclinations. The cover art’s pretty rad, too. I vividly remember watching Melinda Beck’s creepy-yet-cute animations on Noggin/Nick Jr. as a little kid, and her work suits the sound of this EP quite well.

The band’s fondness for childhood and travel are the focus of Children Can Be So Cruel, comprised of school yard punk chants and multilingual folk songs. The recording quality’s a lot cleaner here than on the other records I’ve listed, which gives the record a spaced-out and eerie atmosphere.

Children opens with “Three Times Fast,” a deadpan krautrock tune with sinister undertones, but quickly delves into international fare. There’s “I Tanz Jo Net",” a German folk tune loaded with glitchy drum machine, and “Hai Cium Dong,” in which Topper wails in Javanese over polyrhythmic percussion and hypnotic cello. The latter is easily this record’s most impressive offering, with glimmers of Bikini Kill and Talking Heads breaking through the song’s surface without diluting its source material. “Get In” finds Flanagin dipping into Bill Frisell’s palette of Americana-influenced jazz, hammering out bluesy riffs on an acoustic guitar while his bandmates wordlessly scat in falsetto. It should sound annoying in theory, but the end product’s pretty charming. Check it out here.